My blog post about First Nations programs, events and exhibitions in libraries, archives and museums that discuss subject matter that White settlers may find “confronting” or “difficult”

“I can’t own your uncomfortability” – Aunty Charmaine Papertalk Green

Several months ago I asked fellow museum, library and archives folks on Twitter, how do we engage audiences to enter uncomfortable spaces? Especially, relating to First Nations people and the impact of ongoing invasion.

I asked this because I was recently involved in a museum program for university students where we discussed the Stolen Generations and intergenerational trauma and after the program, one of the students anonymously commented on a feedback form that they felt like they were being reprimanded and made to feel bad for being White. I found this to be an odd response as we were just discussing a reality and an issue that affects many, many First Nations people, but they chose to disengage because it made them uncomfortable. This made me worried that White fragility will always get in the way of settlers engaging with programs that challenge the colonial structures that benefit them. This made me worried that White fragility is more of concern to some people than the truth.

I previously experienced this when I was ask to write something about James Cook and I wrote that he represents the start of invasion to many First Nations people and this was changed to he represents that start of the colonial encounter to many First Nations people. I felt that this language was soft and dishonest, but I can understand why it was chosen and that was out of fear of any potential backlash caused by White fragility. Nevertheless, it is concerning that White feelings are privileged over First Nations oppression. Furthermore, what are the implications for us working in libraries, archives and museums trying to ensure that historically suppressed and marginalised voices are prominent part of the history constructed and conveyed by the collections held in theses institutions?

In regards to First Nations people, how our history, culture and communities has been represented in libraries, archives and museums has been historically governed by settlers particularly white settler men and because of this we have been represented through a colonisers lens which reflects the values and beliefs of mainstream settler society. But thanks to the tireless work of First Nations people in these spaces before me and many allies this has changed and continues to change, however if the First Nations output from libraries, archives and museums is scared of white settler feelings then our representations are still in a way governed by white settlers.

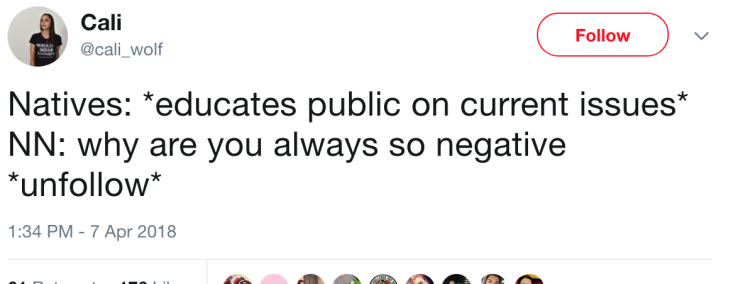

Be more positive

Of course, tone policing is not new. I have heard people say many times if First Nations people were more inviting and less “confronting” with their stories, then people (white settlers) would engage with them more. Although, this is flawed, because it puts the responsibility on us, First Nations people. Instead of asking ” why are you making me uncomfortable”, settlers should ask “why do I feel uncomfortable” when engaging with First Nations stories and histories.

Additionally, even when manifestations of our cultures and our histories focus on the positive, it can still threaten White fragility. For instance, the opening ceremony of the 2018 Commonwealth Games included culture and performances by several different First Nations cultural practitioners and communities, which even though it was celebratory and by no means critical of colonisation, it still caused a negative reaction among white settlers. Social commentators were offended by the mere inclusion of First Nations culture and the disruption of our invisibility.

Who’s discomfort?

All of this can imply that white settlers are the intended audience for First Nations output from libraries, archives and museums. For instance, I was recently talking with a white settler curator about how it is becoming more common for exhibitions to include relevant First Nations languages and she said she was worried that it can be confusing for the exhibition visitors. Undoubtedly, she was talking about White settlers when she was saying visitors and my initial reaction to this was “not everything is about you”. But exhibitions have been, in many cases, about her as her epistemology, her experiences and her language are considered the default in mainstream settler society and therefore have been reflected in a majority of exhibitions. And because of this, she is more concerned with potential white settler discomfort caused by confusion than suppression of First Nations languages.

In addition to this, discussions about discomfort in libraries, archives and museums rarely touch on First Nations peoples’ discomfort that could stem from keeping our cultural heritage in very colonial buildings, describing or classifying our cultural heritage in ways that are alien to our world-views, the implementation of confusing access guidelines and the celebration in libraries, archives and museums of people many of us deem to be violent, oppressive colonisers.

How do we engage audiences to enter uncomfortable spaces?

I genuinely asked that question several months ago because I know many people have done great work in regards to this and want to hear their thoughts because we need many colonial structures to change and change comes from being uncomfortable which will never happen if White fragility gets in the way and is prioritised. How do we get audiences, especially White settler audiences to understand discomfort is temporary, oppression is not?

Further reading

‘Difficult’ exhibitions and intimate encounters

By Nathan Sentance